- The FIA has begun its investigation of the Romain Grosjean crash at Bahrain last weekend, and results of that investigation are expected in six to eight weeks.

- Grojsean somehow was able to free himself from his burning car and escape with burns to the back of his hands.

- Grosjean hopes to return to his car and race in the F1 season finale at Abu Dhabi on December 13. It will likely be Grosjean’s final F1 race, as he does not have a ride for 2021.

Fans and even racers use words like “miracle” and “lucky” to describe Formula 1 driver Romain Grosjean’s great escape from a horrific crash into a steel guardrail and the resulting fireball on the first lap of the F1 Bahrain Grand Prix on November 29.

After all, how else can even the most ardent race fan or driver possibly explain how Grosjean extricated himself from an inferno-engulfed F1 race car in 28 seconds and walked away—with a little aid, of course—with just burns on the back of both hands?

Luck and miracles are not what the FIA Safety Department wants to rely on. Those words are nowhere in the safety handbooks and guidelines. Ultimately, it will be up to the FIA to determine what went right and, more important, what went wrong in that first-lap crash at the F1 Bahrain Grand Prix.

The sport, on the other hand, escaped with a near miss. The result could have been a lot worse.

“Neither luck nor divine intervention was the reason he survived,” said David Ward, a former longtime director general of the FIA Foundation, which organized much of the research work into motor racing safety through the FIA Institute. “That [Grosjean] was soon able to post a smiling interview from his hospital bed is because since 1994, the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) [has] applied a ‘Vision Zero’ approach to safety.”

That wasn’t always the case. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the FIA showed little or no interest in safety at a time when fatalities were frequent and when seatbelts were relatively new; barriers were often just hay bales. Medical help amount to little more than ill-equipped ambulances.

This began to change because of campaigns by the drivers, led early on by three-time F1 champion Jackie Stewart, to improve the situation. New technology, such the carbon-fiber monocoque and fuel cells transformed the structural integrity of F1 cars, and the risks of fire and cockpit integrity faded.

Former F1 chief executive Bernie Ecclestone recruited Prof. Sid Watkins in 1978 to oversee medical response, and that side of the sport improved to such an extent that no F1 driver died in a Grand Prix car at a race between 1982 and 1994.

Elio de Angelis was killed in a crash during a test session at Paul Ricard Circuit in France in 1986, but at that time testing did not adhere to the same safety regulations as racing. And then came the Italian Grand Prix at Imola in 1994, and the deaths of Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna. The FIA president at the time, Max Mosley, asked Watkins to establish a research group to carry out a comprehensive review of all F1 safety, and the group adopted an evidence-based approach to solving problems.

The FIA’s work is not always accepted without a fight, as was the case with the HANS (head and neck support) device, which was introduced in 2003, and again with the halo, which Mosley’s successor, Jean Todt, forced the sport to accept in 2018.

This crash will likely result in more changes to the track safety manuals. The steel guardrail pierced by Grosjean’s car will likely come under the microscope. According to the FIA, an investigation is under way and is expected to take up to two months.

Sebastian Vettel Reacts

“You have to be respectful of the fact that obviously the investigation will be very thorough and will take some time to probably get answers in general,” four-time Formula 1 champion and Ferrari driver Sebastian Vettel said on December 3 in Bahrain. “There’s no rush on that and no disappointment. But I think it probably showed on Sunday that we are sitting at two different sides of the table.”

“We are the ones driving the cars, and we are exposed to the risks and the limits and so on. And everyone who is watching sometimes criticizes the fact that it’s not dangerous enough, not exciting enough. But I think a certain risk will always be there. As much as we can take away, it will be good. It’s good to see there’s continuous effort being made, and these chances that we get with accidents are taken seriously to try and improve.

“It’s a reminder of the fact, hopefully for the other side, that it’s not just objects in the car. We are human beings, and we put our lives on the line. But I think that’s something we are happy to do because we have a great passion for what we do.”

The Investigation Begins

On December 3, the FIA announced an outline for its investigation. The FIA Safety Department said that the Grosjean investigation will follow the same procedures as any of the 30 or so serious accidents the FIA investigates annually, worldwide.

The investigation will examine all areas, including competitor safety devices such as the helmet, HANS, safety harness, protective clothing, survival cell, headrest, in-car extinguisher system, and the halo frontal cockpit protection device. Analysis will also include chassis integrity and the safety barrier performance for an impact of that energy and trajectory. It will also assess the role of the track marshals and medical intervention team.

The FIA is working with Liberty Media, the Haas F1 Team, and the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association, which has already been contacted for input. The FIA’s final report will be based not on divine intervention, but around the science behind what happened and the data that was gathered.

Lots and lots of data.

The FIA says that Formula 1 uses more data-gathering instrumentation than in any other championship. FIA researchers will be able to study various video streams, including video produced by a high-speed camera which faces the driver and films at 400 frames per second. The resulting video will show investigators, in super slow motion, what happened to the driver during the accident.

This content is imported from Twitter. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

And those videos, say some drivers, need to stay with the investigators.

Vettel and Renault F1 driver Daniel Ricciardo led a contingent critical of how the near-tragic event was played out in the media on race day with seemingly constant replaying of the crash, even before the full extent of Grosjean’s injuries were known.

“Sometimes here and there, there should be a bit more respect. Showing the incidents over and over, I think was not the way of doing that,” Vettel said. “For sure, everyone saw that Romain was fine, but still it doesn’t change the fact that there’s kids watching and so on. I think it wasn’t a nice thing to watch in general if you imagine that actually there’s a soul in that car who’s trying and fighting to get out.”

Data will also be gathered from the in-car Accident Data Recorder (racing’s version of air travel’s black box), which will reveal the speed and g-forces on the car. Drivers wear in-ear accelerometers that are custom made for each driver to fit inside a driver’s ear canal to measure the movement of his head in a crash.

“As with all serious accidents, we will analyze every aspect of this crash and collaborate with all parties involved,” FIA safety director Adam Baker said. “With so much data available in Formula 1, it allows us to accurately determine every element of what occurred, and this work has already begun. We take this research very seriously and will follow a rigorous process to find out exactly what happened before proposing potential improvements.”

The FIA Serious Accident Study Group, an organization chaired by FIA president Jean Todt, will then process the information with oversight by the FIA safety department and FIA sporting department heads. Doctors, engineers, researchers, and officials are all represented in the meetings. Accidents are analyzed from technical, operational, and medical sides, and measures are then taken.

“The crash began with a driver mistake, as Grosjean turned into the path of another competitor,” former FIA director general Ward said. “But from the moment of that collision, Grosjean began a journey through layers of defense that the FIA has systematically developed to mitigate the risk of injury. Although some defenses failed, Grosjean avoided serious injury, or worse, by a combination of the halo cockpit protection system, the chassis survival cell, his helmet, and fire-proof overalls. And, finally by the rapid response of the medical car team of Alan van der Merwe and Dr. Ian Roberts.”

The car hit the barriers at an angle that even computer simulations failed to simulate in such a location.

The level of sophistication now used by the FIA’s safety engineers is far more advanced than many people think, and there are set standards for barrier placement and inspections to make sure that the required word has been done. The FIA actually uses software that has been specifically designed to predict what is best in terms of barriers, given the risks involved.

The normal expectation in that area of track would be for incidents on the outside of the circuit, rather than impacts on the inside. The point of impact is about 390 feet from the exit of the corner and so in normal circumstances an out-of-control car which has lost control exiting the corner, after riding over a curb, would not hit the barriers with much energy remaining.

The problem was that Grosjean lost control as a result of a tangle with Daniil Kvyat at around 260 feet from the point of impact, and the car did not have time to spin. That resulted in an impact speed of 137 mph and a g-force which the FIA reported to be in a range measured as high as 56 g by the sensors in the car that alert the medical car about the forces involved and flags incidents above a certain limit.

“It was a scary moment,” Kvyat said. “At first I was really angry that he came across [the track] like this. I thought, ‘What is he doing?’ But then my mind changed immediately when I saw in the mirrors the fire. I was just hoping he was OK. I immediately didn’t like what I saw in my mirrors and I am glad he’s OK, honestly. It just reminds you that what we do is dangerous.”

The Impact

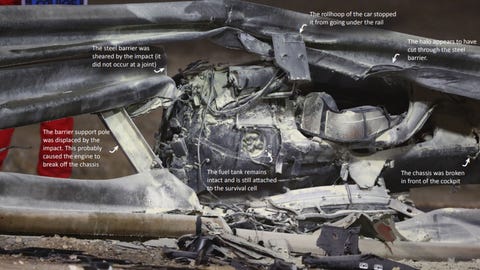

From the available footage, it is difficult to tell the actual angle of the impact, but the nose of the car deformed as it is intended to do in a crash. The forces were so extreme that the front of the chassis can be seen to have broken just in front of the cockpit. However, the break may not have been complete, because the alignment of the two parts remained the same. When Grosjean emerged from the wreck he was minus his left boot, which one can suggest may have been trapped by damage to the front of the monocoque.

The car turned as it hit the barriers, and the bottom two steel guardrails were both torn apart. The rear of the car appears to have hit at a point where there was a steel support pillar going into the ground. This is probably what caused the rear end to shear off, breaking the six solid bolts that attach the engine to the rest of the chassis. This part of the car stayed on the track-side of the barrier, while the front end went almost completely through to the outer side of the barrier. However, the top rail remained in place; it was deformed by the roll hoop of the car and by the halo device, which cut into the steel. These two elements meant that Grosjean was not decapitated by the rails, as has happened a number of times in F1’s distant past.

The sudden deceleration of the car was such that Grosjean was likely stunned, but the HANS device ensured that his head and neck did not break. The deceleration may also have been helped by the fact that the barriers helped to absorb the energy by giving way before they fractured. It may not seem much, but that may have helped when compared to a similar impact with a concrete barrier.

The impact damaged the fuel tank. One photo shows that the breather valve—a valve opposite the valve where the fuel goes into the tank—was no longer in place. That suggests that the forces were such that the fuel cell twisted sufficiently in the impact to cause it to become detached. Some have suggested that although the fire looked very large, it was not big enough to have been the full 100 kg (220 pounds) of fuel that the cars start the race with. Fuel likely remained inside the fuel cell, which is usually divided into different sections. Some of these may have been damaged, but the whole cell seemed to be in place.

“We had a fuel fire, which is something we haven’t had for a very long time,” said F1 sporting director Ross Brawn. “With fuel cells incredibly strong, I suspect that came from a ruptured connection. We need to look at it. Surprisingly, it looked a big fire, but those cars are carrying 100 kilos of fuel at that stage. I think if 100 kilos had gone up, we would have had a massive fire. So, for me, that was a fire of a few kilos of fuel, not 100 kilos.”

Whatever the case, there was still a substantial fire, and Grosjean had very little time to get out. He had to deal with his seatbelts, and the various lines that are attached to a driver when he is the cockpit.

For Grosjean, his own preseason safety training also came in handy.

Drivers have to pass a five-second evacuation test before they are allowed to drive in F1, but obviously factors in the Grosjean crash were complicated by the circumstances. Grosjean might have tried to get out and initially found that the damaged barrier was slightly blocking his exit. It required him to change the angle at which he was getting out, and then he could squeeze between the car and the barrier. The fact that he managed to stay calm and did not panic helped to save his life.

By the time Grosjean was able to climb out of the cockpit on the other side of the barrier, Dr. Ian Roberts had arrived on the scene, along with a fire marshal who was there just before him. Roberts’s first action was to get the fire marshal’s extinguisher working and pointing at the right place, which allowed the doctor to try to get into the fire despite the intense heat. He was not burned himself, but he did admit afterward that things did melt.

Grosjean had similar problems. His visor was opaque because partially melting in the heat. When the pair stumbled out of the fire, medical car driver Alan Van Merwe was seen spraying them both with an extinguisher to make sure that neither had any clothing burning. The medical car arrived 10 seconds after the impact.

“It was a very odd scene where you’ve got half a car pointing in the wrong direction and just across the barrier, and massive heat,” Roberts said. “I could see Romain trying to get up. We needed some way of getting to him. We’ve got the marshal there with an extinguisher and the extinguisher was just enough to push the flame away as Romain got high enough to then reach over and pull himself over the barrier. He was very shaky and his visor was completely opaque and, in fact, melted.”

And the halo did its job by keeping debris created in the impact from striking the driver.

Lewis Hamilton Credits F1 with “Amazing Job”

“I’m just so grateful that the halo worked,” seven-time F1 champion Lewis Hamilton said. “I’m grateful that the barrier didn’t slice his head off. It could have been so much worse. It is a reminder to us and hopefully to the people that are watching at home that this is a dangerous sport. It shows the amazing job that Formula 1 has done, the FIA have done over time to able to walk away from that.”

But there remain questions that need to be answered. Why was there a fire given that the fuel cell should not have allow fuel to spill, even with the huge impact involved?

The second question relates to the barriers. The Bahrain International Circuit hosted its first F1 race in 2004. It was homologated by the FIA when it was designed, and so the placement of the barriers should not be seen to be an issue. The fact that the barrier was there in the first place is an indication that there was at least some expectation that a car could go off there, although it is clear that he angle and the force were not what was anticipated.

THE FIA’S OFFICIAL STANDARDS: SAFETY BARRIERS

Whether a steel barrier was the right barrier for that spot on the course is open to question. The crash revealed that by definition it was not the right barrier because of what happened. But were the alternatives better? Would Grosjean have been killed in the impact if it had been a concrete barrier, a SAFER barrier, or a Tec-Pro modular barrier? The angle and the force might have been such that the metal barrier will turn out to have been the right option. What is clear is that in the history of F1 in Bahrain, over a 16-year period (with 15 races), no one had ever hit the barrier at that point before.

“In general, the choice between steel guardrails and concrete walls on a straight section of track is made considering the drainage, signalling and service road requirements, and the nature of the ground,” said F F1 race director Michael Masi. “I would prefer not to comment further until we have concluded our investigation.”

Could That Crash Happen Elsewhere?

Could a Grosjean crash and fireball happen in, say, IndyCar on one of its road or street courses?

There are, despite all the technology and all the work, situations in which motorsport can never be fully safe because cars going at speeds of more than 200 mph are inherently dangerous—and always will be.

The NTT IndyCar Series turned down Autoweek’s requests for an interview with IndyCar safety personnel in regard to that series’ track inspection procedures and the use of steel guardrails, concrete barriers, and SAFER barriers at road and street courses where the series competes.

“It would be premature to comment while Formula 1 continues its investigation,” said IndyCar vice president of communications Dave Furst. “We do, however, expect to receive their findings and will review [them] internally.”

Everything There Is to Know about the Armco Barrier

Let’s look at the accident itself: not too complicated. Charging up on a bottleneck of slower cars, Grosjean dove to the right of the track just past Turn 3 on the first lap. He struck a blameless Daniil Kvyat, and the contact sent Grosjean on a trajectory toward a part of the fencing that no one was supposed to hit; hence there were no soft barriers such as a tire wall or a foam-backed “soft wall.”

This content is imported from Twitter. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

He hit steel—it’s called an Armco barrier, as Armco has become a generic term for long, seamless fencing used not only on your neighborhood roads but on Formula 1 tracks and most every other type of permanent road course there is.

Why? Because it works, and it is comparatively cost-effective. According to Armco Barrier Supplies of England: “Crash barriers first rose to prominence after their introduction to the sport of Formula 1 as part of the Grand Prix Drivers Association’s ongoing safety campaign of the late ’60s and ’70s. Installed across numerous F1 circuits, the investment in Armco barriers quickly paid off, saving the lives of both race drivers and spectators.

“After their success in F1, the barriers were later added to motorways across the U.K. Used on roadsides and central reservations, the barriers were erected to contain accidents and reduce the risk of cars colliding with oncoming traffic on the other side of the carriageway.

“Quick to manufacture and easy to install, crash barriers have been successfully implemented on motorways and roadsides up and down the U.K. Also extensively installed across the rest of Europe and parts of America. The invention of safety barriers and their comprehensive use has undoubtedly resulted in the prevention of countless fatalities. Barriers not only protect drivers and passengers, but pedestrians as well.”

Armco, before you ask, dates back to 1899, when the company was founded as The American Rolling Mill Company (ARMCO) in Middletown, Ohio, where it operated a production facility.

Armco can be one strip of steel, two, or, in the case in Bahrain, three that are very closely spaced. The Haas F1 car was aimed at the small separation between the bottom strip and the middle strip and made its own opening, shaped at the top like the relatively new halo, a Y-shaped bar that protects the driver’s head. Without it in the Grosjean crash, this story would be an obituary.

Back to Armco: The regulations as designated by the FIA, the sanctioning body for F1, to hold an F1 race require that your track must be a Level 1. Few tracks are Level 1. The only ones in the U.S. are Circuit of the Americas in Austin, Texas, and the road course at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, which used to host F1 and very well may do so again, now that Roger Penske is the owner of the facility.

There are multiple tracks in the U.S. that are Level 2, including WeatherTech Raceway at Laguna Seca, Lime Rock, Road Atlanta, Portland, Sonoma Raceway, Saint Petersburg, Road America, New Jersey Motorsports Park, Barber Motorsports Park, Detroit Belle Isle, Long Beach, and Mid-Ohio.

Even Le Mans is a Level 2, largely because of its length—the FIA doesn’t like to certify any track longer than seven kilometers, or 4.35 miles, because of the difficulty in manning such a long track with the proper safety personnel. That’s why the Nürburgring Nordschleife in Germany no longer hosts F1.

What is the difference between a Level 1 and 2, and for that matter, Levels 3 to 8, the last of which certifies ice racing tracks? It is based on a power-to-weight ratio, meaning how much horsepower a car has, as compared to how heavy it is. Level 1 is 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds) of weight per horsepower, which means F1 cars, which are very powerful, and very light.

Level 2 is for cars with 1–2 horsepower per kilogram. That means IndyCar racing, and of course, any slower cars like those in the IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship. Level 3 is 2–3 horsepower per kilogram.

Bahrain, of course, is an FIA Level 1 track, one of 44 in 30 nations. (The license expires every few years, and there may be some Level 1 or 2 tracks that aren’t hosting events and let the license drop until they do—understandable, since it is a six-figure investment.)

And, as such, Bahrain is state of the art. At the beginning of 2000, Crown Prince Sheikh Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa, Honorary President of the Bahrain Motor Sports Association, gave the order to build an F1 track and hired Tilke Engineers & Architects to build it. Tilke has built the majority of F1 tracks around the world, from Korea to COTA in Austin. Construction started on Bahrain in 2002 and was ready for the first Grand Prix in 2004. Uniquely, the track can be divided into several shorter tracks that can operate simultaneously, meaning you can have a club race on one track, a school session on another, and testing on another. The Grand Prix track is 3.361 miles long.

The FIA specifies fencing requirements in its regulations. “As a general principle, where the estimated impact angle is low a continuous, vertical barrier is required, and where it is high energy-dissipating devices and/or stopping barriers.” Where Grosjean crashed, it is considered a “low” chance of crashing, and as such, soft walls or tire barriers were not required.

As far as those “continuous, vertical” barriers go, when it cones to Armco barriers the FIA specifies that the bottom rail must almost be touching the ground, more a nod to motorcycle racers, to keep them from sliding under a fence, and the Bahrain fence was properly low. And the gaps between the rails must be almost touching, which the rails were in Grosjean’s case—you can see them on either side of the crash site. It seems likely to suggest that the Armco worked better than, say, solid concrete, as the Armco did dissipate some of the energy, as bizarre as that seems.

The Halo

What really saved Grosjean’s life is the halo. Had that crash occurred in 2017 or earlier, before the titanium halo was mandated, it is likely that Grosjean could not have survived. There simply would have been no protection for his head against the barrier. “There’s no doubt the halo is the factor that saved the day,” F1’s Brawn said. The hole in the barrier, at the top, was halo-shaped.

Multiple incidents over the years in a variety of open-wheel series led Formula 1, the chief innovator where cost is no object, to develop the halo in 2016 and 2017 and mandate its use in 2018.

Much as the death of Dale Earnhardt in 2000 caused NASCAR to improve safety, the death of Jules Bianchi encouraged F1 to proceed with the halo. Bianchi suffered a serious head injury in 2014 when his car slid off the wet pavement of the Japanese Grand Prix and into a piece of construction equipment, and he died nine months later. Even if a halo might not have saved Bianchi, safety advocates asked, how could it have come out any worse?

It does seem likely that a halo would have saved IndyCar driver Justin Wilson, who died in 2015 at Pocono when a large piece of debris from a crashed car in front of him rose through the air and landed on his head. And years earlier, Cristiano da Matta’s career was curtailed in 2006 when he hit a deer at Road America in Wisconsin. The deer entered the cockpit, causing head injuries to da Matta that kept him in the hospital for nearly two months.

IndyCar and F1 are not the only open-wheel series that mandates a halo device, which vary slightly from one series to the next, but are similar in design and function. In a Formula 2 race at Catalunya, Nirei Fukuzumi’s car landed atop Tadasuke Makino’s halo, and in the Belgian Grand Prix F1 race, Charles Leclerc’s halo was struck by Fernando Alonso’s airborne McLaren. Both drivers emerged with no serious injuries and credited the halo for saving their lives.

The halo met with substantial kickback from drivers at first, saying it messed with forward vision, and they wondered aloud how quickly they could get out in an emergency. The FIA required drivers to be able to exit the car in five seconds, then upped that to seven when the halo was introduced.

Even Grosjean himself called the halo “annoying” in 2017. Now, he has changed his mind. “It’s the greatest thing in Formula 1,” he said from his hospital bed, a scant six hours after the crash, when he posted a video to Twitter, his finger wrapped for minor burns which he likely got when he grasped the hot Armco barrier to jump over the top of it.

Of course, the halo isn’t the only safety device worth mentioning. Tracks are increasing their use of soft walls, or SAFER Barriers (SAFER standa for Steel And Foam Energy Reduction), which consist of a rigid surface backed by blocks of crushable, replaceable foam. Cars like NASCAR Cup cars weigh more than 3500 pounds, and the SAFER barrier has undoubtedly saved lives since it was first installed at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 2002, during Tony George’s reign. That, coupled with the HANS, or Head And Neck restraint System, which protects the head and neck in a crash that results in sudden deceleration, have helped to mean no NASCAR fatalities since Earnhardt in 2000.

The High Cost of Being Safer

As far as the soft walls go, it costs about $ 400 per foot to install a SAFER barrier the last we checked, prohibitive for many tracks except in high-risk areas. There are alternatives, from stacks of old tires—permitted by the FIA if properly bundled—to cheaper barriers.

One racer who is trying to address this problem is R.J. Valentine, a longtime sports-car competitor who has raced in the SCCA, IMSA, and Trans Am series and was on the winning team for the 2009 Rolex 24 at Daytona. Several of his businesses involve karting, and he developed the KISS (Kart Impact Safety System) for kart tracks. He has adapted the technology for the ProLink safety barrier, a simple, relatively inexpensive soft wall that can be used on a variety of tracks.

The barriers are made of half-inch polyethylene, and they are designed to be filled partly with water. Each four-foot barrier weighs 73 pounds, making for easy installation and replacement in case of damage. Fill the barriers to one-quarter capacity with water, and each one weighs 500 pounds, heavy enough to absorb a solid hit. Best of all, the barriers only cost, including installation, about $ 70 per foot.

Finally, there are two other factors that can’t be overlooked in Grosjean’s survival. First is the fact that it was the first lap, and the safety car, which follows the pack for that lap, was right there with strong fire extinguishers and a helping hand in getting Grosjean over the barriers. Their efforts were admirable.

And second, Grosjean was awake, alert, and his arms were fine, allowing him to be able to unbuckle his safety harness and exit the car. Had he been knocked out, even for less than a minute, this story, as mentioned, might be an obituary instead of a tribute to all the things that helped him survive. By any metric, that was an unsurvivable crash. But he did.

Miracles, aided by technology, do happen.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io