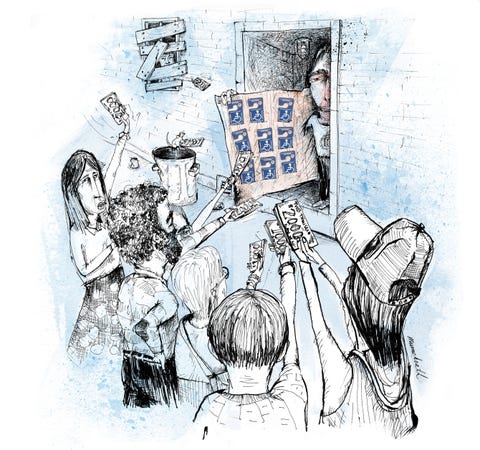

Illustration by Darcy MuenchrathCar and Driver

From the June 2020 issue of Car and Driver.

Since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990, those ubiquitous blue parking permits have allowed drivers with disabilities to park in prime spaces, often for free and with no time limits. It didn’t take long for scammers to realize that disability placards could also be a valuable commodity for those whose only affliction is a distaste for following the rules. Across the country, the rampant illegal use of these placards makes life even more challenging for disabled drivers, as it leaves fewer spots available for those who need them.

The black market for disability placards exists online as well as on street corners, and placards can sell for anywhere from $ 50 to $ 2600 each. Tiffany James, communications manager at the Parking Authority of Baltimore City, says that before the city got a handle on the situation, “If you needed cash, you could find a car displaying a disability placard, smash the window, grab the placard, and sell it for $ 100.” For the buyer, that permit could be worth $ 10,000 a year in free parking in a big city.

In the absence of federal standards, states and municipalities are writing their own rules to discourage placard theft, but the regulations are all over the map. Massachusetts, New Mexico, and South Carolina require ID photos on disability placards. In New Jersey, drivers caught using a placard illegally may be subject to a fine of up to $ 10,000 and 18 months in prison. In Los Angeles, officials conduct compliance checks four times a month throughout the city. Deputy chief of parking enforcement Richard Rea says his team confiscated 702 fraudulent placards in 2019. And in April of last year, the city council voted to hit violators with an $ 1100 fine.

One proposed solution aims to disincentivize abuse by granting free parking only to those with disabilities that restrict their ability to use common payment infrastructure (e.g., they can’t insert coins into a meter due to a lack of fine motor control or readily approach a kiosk due to a wheelchair). Understanding that this would face a lot of pushback from the disabled community, advocates suggest that any revenue earned from this change be invested in safer sidewalks, better curb ramps, and audible devices at pedestrian crosswalks. They also point out that advancements such as meters that take credit cards and smartphone parking apps have made paying for parking easier. James says that within a month of requiring placard holders to pay for parking and adhere to time limits as part of a 2014 initiative, “Baltimore’s problem dried up.”

Permit Poll

Lack of accessible parking has real consequences, as evidenced by the responses to a national survey of people with disabilities conducted in late 2017.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io